The Literary Tradition Continues . . .

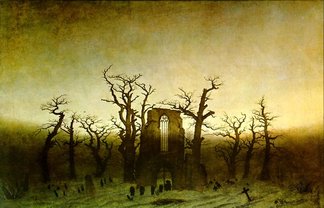

We skip a century here between Milton and the next development in our brooding anti-hero, thanks to the excess of Reason--even in literature--during the Enlightenment. But an excess of anything breeds its opposite and so, in the middle of the 18th-century, the Gothic movement is born. In English literature its 'birth' is usually attributed to the wild imagination of Horace Walpole (1717-1797), son of a British Prime Minister and an earl in his own right. On a whim, he had a ruined medieval abbey disassembled and rebuilt on the grounds of his own estate, Strawberry Hill. He and friends liked to sit amidst the ruins on a summer's eve and tell stories of the supernatural, inspired as they were by their surroundings.

Out of that came the first Gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto. It contained all the earmarks of a prototype: the medieval setting; a dark and sinister atmosphere; and, most importantly for our purposes, a mysterious and black-hearted man who was keeping a diabolical secret. Yet that secret made him vulnerable both to internal torment and to exposure, by someone who guessed the secret, to the world at large. At first--and certainly in Otranto--the mysterious man was a villain and, in general, the young couple couldn't hope to find happiness unless he was disposed of, often by supernatural means.

But as the genre became more popular and evolved, ushering in a number of women writers, the man of mystery started to develop characteristics we have come to recognize in Edward Cullen: though he was menacing, he was in pain; he was more often seen as handsome in a darkly brooding way; and he was a fit alternative to the traditional young man in the hearts of our heroines.

Out of that came the first Gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto. It contained all the earmarks of a prototype: the medieval setting; a dark and sinister atmosphere; and, most importantly for our purposes, a mysterious and black-hearted man who was keeping a diabolical secret. Yet that secret made him vulnerable both to internal torment and to exposure, by someone who guessed the secret, to the world at large. At first--and certainly in Otranto--the mysterious man was a villain and, in general, the young couple couldn't hope to find happiness unless he was disposed of, often by supernatural means.

But as the genre became more popular and evolved, ushering in a number of women writers, the man of mystery started to develop characteristics we have come to recognize in Edward Cullen: though he was menacing, he was in pain; he was more often seen as handsome in a darkly brooding way; and he was a fit alternative to the traditional young man in the hearts of our heroines.

And in Germany, Goethe and The Sorrows of Young Werther--

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) has sometimes been called Germany's Shakespeare for the way his countrymen regard his written works. Very much a part of the Sturm und Drang ("Storm and Stress") movement in literature, he wrote a short novel about a young man named Werther who is highly sensitive--to his own pain and to the pain he might cause others. When he falls in love with a young woman already engaged to a man much older than she, his conundrum is excruciating: he cannot be separated from her for his love is too great to afford that pain but to declare himself would cause too much pain to others. At last he realizes one of the three must die--and so he nobly takes his own life. The novel was a huge bestseller, inspiring young men to want to be Werther, young women to want to fall in love with/be loved by a Werther and even caused a significant number of copycat suicides. In many ways, this book, as it spread across Europe in translation, was the start of the Romantic movement in English literature. In Germany, Goethe had a huge effect on composer Richard Wagner and, through him, on Hitler. What Goethe's novel adds to our brooding hero is the element of suffering--even dying--for love.

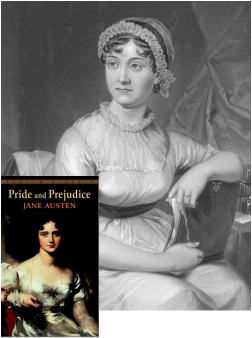

Jane Austen's Contribution

Though she lived in the middle of the era in which Gothic and Romantic influences dominated literature--and we know she read Gothic novels herself: she wrote a scathing parody of them in Northanger Abbey--her own novels tend to be comedies of manners, about young women living in small towns or in the country whose chief goal in life must, by necessity, be to marry and to marry well. Though her novels reward common 'sense' over 'sensibility' (another word for that excess of sensitivity that Werther suffered from), in her most famous book, Pride and Prejudice, her spunky and independent heroine, Elizabeth Bennet, first openly rejects and then falls in love with the somewhat cool and proper Mr. Darcy, causing them both much pain.

Stephenie Meyer has said she based some aspects of Twilight on this novel--and the superior and sometimes smug attitude of Edward Cullen in the book may, at a pretty superficial level, reflect that. But Darcy is a man of logic and reserve who is pained by impropriety and obviousness--he first avoids the Bennet girls because he overhears that Mrs. Bennet intends to make 'good matches' for all five of her daughters. When Lizzie rejects his marriage proposal and scoffs at him, though he is very hurt, it doesn't seem to be because he is experiencing the deep pain of thwarted love but rather he is made distraught by the failure of logic in what seems to be a girl of great good sense. And definitely the more deeply suffering character of Pattinson's Edward Cullen wouldn't fit in an Austen drawing room.

Stephenie Meyer has said she based some aspects of Twilight on this novel--and the superior and sometimes smug attitude of Edward Cullen in the book may, at a pretty superficial level, reflect that. But Darcy is a man of logic and reserve who is pained by impropriety and obviousness--he first avoids the Bennet girls because he overhears that Mrs. Bennet intends to make 'good matches' for all five of her daughters. When Lizzie rejects his marriage proposal and scoffs at him, though he is very hurt, it doesn't seem to be because he is experiencing the deep pain of thwarted love but rather he is made distraught by the failure of logic in what seems to be a girl of great good sense. And definitely the more deeply suffering character of Pattinson's Edward Cullen wouldn't fit in an Austen drawing room.

Are there any influences of Austen's book on Edward Cullen?

His early impatience with Bella because she interests all the other boys (and therefore isn't suitable for him) and because he can't read her mind would not be untypical of Mr. Darcy. Darcy is wealthy and keeps himself separate, like the Cullens. Like Darcy, Edward makes sure the field is clear of other males Bella might be interested in before he makes a move.

Three of the more wrong-headed things he does could also be ascribed to a Darcy influence. The anger that he shows to Bella while trying to keep her away from him in the early part of Twilight would be a function of his 'prejudging' (prejudice) what her reaction to him would be--and he was very wrong. Secondly--and this is likely very true--Meyer was influenced by Darcy's desire to make good Lydia Bennet's elopement with Wickham to create the bizarre and quite out of character scene in Midnight Sun where Edward stages a conversation with Emmett to make sure Ben Cheney and Angela Weber get together for the prom. And finally his taking himself out of the picture in "New Moon" to lessen his own pain and for Bella's own good (supposedly), lying to her all the while, might be a Darcy move. It's also true that Darcy comes to care for Lizzie when she is separated from the female influences and concerns that dominate her family; Edward first opens up to Bella ("I've decided to give up trying to avoid you") when he separates her from her girlfriends in Port Angeles. In general, though there may be some factual details, the passion that governs Edward and Bella's relationship, whether it's off or on, is very unlike Jane Austen's tone.

Three of the more wrong-headed things he does could also be ascribed to a Darcy influence. The anger that he shows to Bella while trying to keep her away from him in the early part of Twilight would be a function of his 'prejudging' (prejudice) what her reaction to him would be--and he was very wrong. Secondly--and this is likely very true--Meyer was influenced by Darcy's desire to make good Lydia Bennet's elopement with Wickham to create the bizarre and quite out of character scene in Midnight Sun where Edward stages a conversation with Emmett to make sure Ben Cheney and Angela Weber get together for the prom. And finally his taking himself out of the picture in "New Moon" to lessen his own pain and for Bella's own good (supposedly), lying to her all the while, might be a Darcy move. It's also true that Darcy comes to care for Lizzie when she is separated from the female influences and concerns that dominate her family; Edward first opens up to Bella ("I've decided to give up trying to avoid you") when he separates her from her girlfriends in Port Angeles. In general, though there may be some factual details, the passion that governs Edward and Bella's relationship, whether it's off or on, is very unlike Jane Austen's tone.

The English Romantics, with particular attention to George Gordon, Lord Byron

The Romantic movement in England in art and literature occurred very much within Austen's lifetime, yet she was scarcely influenced by it. Not so the rest of its young people. It was, in its own way, a bit like the 1960's and the hippie lifestyle--it affected all aspects of culture, both high and low--and was probably similarly short-lived.

Byron (1788-1824, pictured RIGHT) was perhaps not the best poet of the age but he embodied many of its obsessions in his writings as well as in his life. In fact, henceforth, we're going to call our brooding, dark, mysterious anti-hero ARCHETYPE the Byronic hero--and Edward Cullen is certainly that! Though born with a club foot, Byron was rakishly handsome, a member of the peerage and a rock star in taste and behaviour. He seduced married women, like Lady Caroline Lamb who became a sort of stalker/groupie to him, even after he had publicly rejected her. She called him by an epithet that has stuck: he was, she said, "mad, bad and dangerous to know". He alluded to the 'fact' that he had slept with his half-sister many times; there was even a rumor, which neither of them dispelled, that he was the father of her daughter.

One of his best friends and a fellow poet was Percy Bysshe Shelley; he had left a wife and children to run away with Mary Godwin who later became Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein. Indeed, the friends who happened to be together on the storm-rocked shores of Lake Geneva during the so-called 'haunted weekend' were Byron, Shelley, Mary Shelley and John Polidori, Byron's personal physician and friend for many years. Inspired by the Gothic novels of the time, they each set themselves the task of coming up with a story or poem with the supernatural as its theme. We don't know what happened to the efforts of Byron and Shelley that weekend but Mary started Frankenstein, the only lengthy work she ever wrote, and Polidori wrote "The Vampyr", a 20-page tale that is considered to be the first vampire story in English.

Byron (1788-1824, pictured RIGHT) was perhaps not the best poet of the age but he embodied many of its obsessions in his writings as well as in his life. In fact, henceforth, we're going to call our brooding, dark, mysterious anti-hero ARCHETYPE the Byronic hero--and Edward Cullen is certainly that! Though born with a club foot, Byron was rakishly handsome, a member of the peerage and a rock star in taste and behaviour. He seduced married women, like Lady Caroline Lamb who became a sort of stalker/groupie to him, even after he had publicly rejected her. She called him by an epithet that has stuck: he was, she said, "mad, bad and dangerous to know". He alluded to the 'fact' that he had slept with his half-sister many times; there was even a rumor, which neither of them dispelled, that he was the father of her daughter.

One of his best friends and a fellow poet was Percy Bysshe Shelley; he had left a wife and children to run away with Mary Godwin who later became Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein. Indeed, the friends who happened to be together on the storm-rocked shores of Lake Geneva during the so-called 'haunted weekend' were Byron, Shelley, Mary Shelley and John Polidori, Byron's personal physician and friend for many years. Inspired by the Gothic novels of the time, they each set themselves the task of coming up with a story or poem with the supernatural as its theme. We don't know what happened to the efforts of Byron and Shelley that weekend but Mary started Frankenstein, the only lengthy work she ever wrote, and Polidori wrote "The Vampyr", a 20-page tale that is considered to be the first vampire story in English.

How his Dramatic Poem "Manfred" Help Set the Parameters for the Byronic Hero--

On the LEFT is a painting inspired by Byron's "Manfred" but, although our hero is clutching his hair in a way that might seem familiar from Page One and is clearly suicidal, the colour of the scene is altogether too bright and sunny to match this poem.

As we meet Manfred, he is in almost all respects an immortal. By birth he was a noble and a man of superior intellect; he found no peace or joy in the ordinary pursuits of life: a wife, family, interaction with his fellow man. By conjuration and study, he learned the secrets of the universe and now he inhabits a castle of his own devising on the top of an Alpine mountain called Jungfrau (it means 'young woman' in German and the mountain is shaped like a breast).

As the poem opens, he conjures seven spirits of the elements to help him achieve forgetfulness, oblivion. This he requires because he has brooded, suffered, been sleepless for an eternity; as he says, "Good, or evil, life, powers, passions, all I see in other beings, have been to me as rain unto the sands, since that all—nameless hour." He bears a guilt, a sin committed in that "nameless hour", that he won't reveal. But these spirits he has controlled and now summoned show only contempt for him and, when he falls into a swoon, one pours a distillation over him that is made up of his own essence and condemns him to further Hell on earth, as well as denying him the ability to die.

He is so like Milton's Satan and yet Byron has him say that his last purpose is to justify the ways of himself to himself--he is too arrogant, powerful and despairing to have to justify himself to God. But there is one being, now dead--a suicide, it seems--to whose spirit he must confess and ask atonement: his sister Astarte. She it seems was his partner (or victim) in the sin committed in that nameless hour but, though she is summoned, she is silent in response to his pleas for forgiveness. All she grants him is the promise of death. In his last moments, a holy abbot and a spirit of Hell wrestle over his end, to save or condemn him. He declares he is beyond them both and, with his final words, tells the abbot, "Old man, 'tis not so hard to die."

The moral of the story Manfred himself expresses very early in the poem: "Sorrow is knowledge: they who know the most must mourn the deepest o’er the fatal truth: The Tree of Knowledge is not that of Life." In other words, to have experienced great heights beyond the realm of ordinary mankind, to have knowledge of Good and Evil, takes one away from 'life'. It renders one, as Manfred says, "most sick at heart. . . . The mind which is immortal makes itself requital for its good or evil thoughts, is its own origin of ill and end, and its own place and time."

As we meet Manfred, he is in almost all respects an immortal. By birth he was a noble and a man of superior intellect; he found no peace or joy in the ordinary pursuits of life: a wife, family, interaction with his fellow man. By conjuration and study, he learned the secrets of the universe and now he inhabits a castle of his own devising on the top of an Alpine mountain called Jungfrau (it means 'young woman' in German and the mountain is shaped like a breast).

As the poem opens, he conjures seven spirits of the elements to help him achieve forgetfulness, oblivion. This he requires because he has brooded, suffered, been sleepless for an eternity; as he says, "Good, or evil, life, powers, passions, all I see in other beings, have been to me as rain unto the sands, since that all—nameless hour." He bears a guilt, a sin committed in that "nameless hour", that he won't reveal. But these spirits he has controlled and now summoned show only contempt for him and, when he falls into a swoon, one pours a distillation over him that is made up of his own essence and condemns him to further Hell on earth, as well as denying him the ability to die.

He is so like Milton's Satan and yet Byron has him say that his last purpose is to justify the ways of himself to himself--he is too arrogant, powerful and despairing to have to justify himself to God. But there is one being, now dead--a suicide, it seems--to whose spirit he must confess and ask atonement: his sister Astarte. She it seems was his partner (or victim) in the sin committed in that nameless hour but, though she is summoned, she is silent in response to his pleas for forgiveness. All she grants him is the promise of death. In his last moments, a holy abbot and a spirit of Hell wrestle over his end, to save or condemn him. He declares he is beyond them both and, with his final words, tells the abbot, "Old man, 'tis not so hard to die."

The moral of the story Manfred himself expresses very early in the poem: "Sorrow is knowledge: they who know the most must mourn the deepest o’er the fatal truth: The Tree of Knowledge is not that of Life." In other words, to have experienced great heights beyond the realm of ordinary mankind, to have knowledge of Good and Evil, takes one away from 'life'. It renders one, as Manfred says, "most sick at heart. . . . The mind which is immortal makes itself requital for its good or evil thoughts, is its own origin of ill and end, and its own place and time."

So now we can put together the Byronic Hero ARCHETYPE . . .

and see it in Milton's Satan, Manfred and Edward Cullen (the Pattinson version, rather than the Meyer version), as well as being able to use it to predict some other Byronic heroes Meyer says she referenced in the later books.

- He is superior to ordinary men, in intelligence, beauty, experience, power.

- He may be immortal. He is usually charismatic, compelling, desired.

- He is guilty of a crime or sin (even a sin of omission) of some kind, for which he fears he will not find forgiveness. (This fear may drive him to become thoroughly evil: Milton's Satan; Heathcliff for most of Wuthering Heights.)

- He thinks he must remain silent about the sin or crime and this makes him sick at heart.

- He knows more than most men about evil: he has eaten of the fruit of the Tree, whether deliberately or in error. He may choose to live beyond the rules of others because of "the horror, the horror" of that knowledge.

- He may love passionately but she will likely NOT be an ordinary woman. He may be forced to keep this love a secret, even from her. If he acts, he may condemn them both.

- His sufferings cause him pain; he may inflict that pain on others.

- Though he is arrogant and prideful, he often thinks himself a monster (see top image RIGHT). Self-hate leads to hatred of others and more cruelty.

- If he is to be saved--forgiven--it will be by the woman. Though he often tries to stay away from her, his salvation--the promise of paradise, a new Eden--lies with her.

- It is his brooding pride, his self-hatred, his need to be forgiven and his recognition--if it happens thus--that his salvation lies with a woman that makes him so irresistible to women readers in general.*

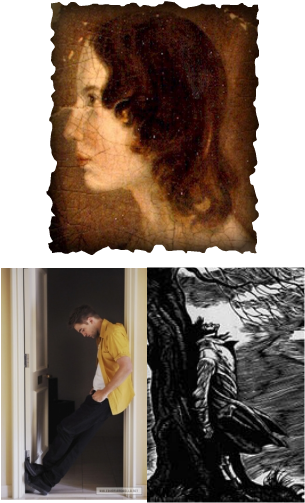

Emily Bronte and the Influence of Heathcliff and Wuthering Heights on the Development of the Byronic Hero--

One of the concrete ways we know how influential Byron and his heroic archetype was on the populace occurred because of his death, prematurely, at 36. For the English--maybe even for most of Europe--it was an event like the death of Buddy Holly for Dan McLean, the death of John Lennon for most of us baby boomers, maybe the death of Kurt Cobain for you. Tennyson, poet laureate of Britain for most of Victoria's reign, wrote that, though he was only 12, it affected him deeply; it was as if the world had darkened. He went into the woods and carved "Byron is dead" upon a rock.

Though she was only six when he died, the Byronic hero must have had a tremendous influence on the reclusive Bronte sisters--Charlotte, Anne and particularly Emily (1818-1848), whose novel Wuthering Heights serves as a great, late Gothic masterpiece with the unforgettable character Heathcliff (LOWER NEAR LEFT, back-to-back with a brooding Rob Pattinson) standing as a real-world Satan in the Miltonic tradition.

Stephenie Meyer has Bella refer to Wuthering Heights frequently in Eclipse, even quoting Cathy's line about how a world without Heathcliff is no world at all; that's the way she feels about Edward. But the comparisons are superficial. Meyer may have been referring to the fact that, like Cathy Earnshaw, Bella has to choose between two lovers in that novel, one rich and one poor--but the parallels are all wrong. Edward Cullen shares Byronic hero traits with Heathcliff, the poor one whom Cathy will pass over--for both their own goods, though she admits they shouldn't live without each other. And the other choice, Edgar Linton, is a refined, dignified and caring man--a perfect love interest in a Jane Austen novel, but no match for the charismatic Heathcliff. And no parallel to Jacob Black.

Meyer is right, as I've been demonstrating, to lump Pattinson's Cullen with Heathcliff, since both are types of the Byronic hero. And the passion between Heathcliff and Cathy, when they are reunited, and Edward and Bella is similar (though the latter is mostly always PG-13).

But Heathcliff's sin is one of omission--either failing to make peace with Hindley Earnshaw earlier in their lives so that Cathy wouldn't have had to marry Edgar to help Heathcliff make a place for himself. Or, more likely, leaving his hiding place on the bench too soon and missing Cathy's whole confession to Nelly, at the end of which he could've laid claim to her himself.

Because he and Cathy are only briefly reunited before her death during childbirth, he is incapable of forgiving himself, letting self-hatred spill out into cruelty and wreaking havoc with the second generation--his own son with the wishy-washy Isabella, Linton Heathcliff; Hindley's orphaned son Hareton; and Catherine Linton, Cathy's daughter with the hated Edgar who, by being born, caused his beloved Cathy to die. He is one of the few Byronic heroes to imitate Milton's Satan and, after great pain, embrace cruelty, making Wuthering Heights a Hell on earth. And he is one of the few who must die to be reunited with the woman he has loved; she comes back for him as a child-ghost, thereby returning them (because of the age of the manifestation) to a state of innocence, and from that moment he knows he is forgiven. His mood lightens and he abandons his Satanic manipulation of the Heights as he waits for death. If Heathcliff and Cathy find salvation at all, it is as two ghosts who (as local rumor has it) roam the moors together, children as they once were, wild and free.

Though she was only six when he died, the Byronic hero must have had a tremendous influence on the reclusive Bronte sisters--Charlotte, Anne and particularly Emily (1818-1848), whose novel Wuthering Heights serves as a great, late Gothic masterpiece with the unforgettable character Heathcliff (LOWER NEAR LEFT, back-to-back with a brooding Rob Pattinson) standing as a real-world Satan in the Miltonic tradition.

Stephenie Meyer has Bella refer to Wuthering Heights frequently in Eclipse, even quoting Cathy's line about how a world without Heathcliff is no world at all; that's the way she feels about Edward. But the comparisons are superficial. Meyer may have been referring to the fact that, like Cathy Earnshaw, Bella has to choose between two lovers in that novel, one rich and one poor--but the parallels are all wrong. Edward Cullen shares Byronic hero traits with Heathcliff, the poor one whom Cathy will pass over--for both their own goods, though she admits they shouldn't live without each other. And the other choice, Edgar Linton, is a refined, dignified and caring man--a perfect love interest in a Jane Austen novel, but no match for the charismatic Heathcliff. And no parallel to Jacob Black.

Meyer is right, as I've been demonstrating, to lump Pattinson's Cullen with Heathcliff, since both are types of the Byronic hero. And the passion between Heathcliff and Cathy, when they are reunited, and Edward and Bella is similar (though the latter is mostly always PG-13).

But Heathcliff's sin is one of omission--either failing to make peace with Hindley Earnshaw earlier in their lives so that Cathy wouldn't have had to marry Edgar to help Heathcliff make a place for himself. Or, more likely, leaving his hiding place on the bench too soon and missing Cathy's whole confession to Nelly, at the end of which he could've laid claim to her himself.

Because he and Cathy are only briefly reunited before her death during childbirth, he is incapable of forgiving himself, letting self-hatred spill out into cruelty and wreaking havoc with the second generation--his own son with the wishy-washy Isabella, Linton Heathcliff; Hindley's orphaned son Hareton; and Catherine Linton, Cathy's daughter with the hated Edgar who, by being born, caused his beloved Cathy to die. He is one of the few Byronic heroes to imitate Milton's Satan and, after great pain, embrace cruelty, making Wuthering Heights a Hell on earth. And he is one of the few who must die to be reunited with the woman he has loved; she comes back for him as a child-ghost, thereby returning them (because of the age of the manifestation) to a state of innocence, and from that moment he knows he is forgiven. His mood lightens and he abandons his Satanic manipulation of the Heights as he waits for death. If Heathcliff and Cathy find salvation at all, it is as two ghosts who (as local rumor has it) roam the moors together, children as they once were, wild and free.

Charlotte Bronte, Jane Eyre and the Domesticated Byronic Hero--

It's in Emily's sister Charlotte's novel Jane Eyre that Stephenie Meyer should've gone to to see more clearly Bella's role in the life of a Byronic hero. Too, Charlotte Bronte (1816-1855) has recently been seen as an early feminist for her creation of the spunky little governess for whom Mr. Rochester was prepared to give up everything.

To start, Mr. Rochester is the typical Byronic hero but tamer than Heathcliff because he has an estate and a reputation to keep up. He has several crimes he's keeping secret; first, there's the parentage of the charming Adele who Jane is brought in to care for. But much more significantly there's the mad wife he keeps locked on the third floor, giving the first half of the novel its Gothic undertones. He is arrogant, almost running Jane down on her way to his manor and cursing her for getting in his way. He is curt to her--and to almost everyone--brooding alone in his study most evenings when he is at home. Jane is meant to be his salvation but he has forgotten an important step in the reclamation of the Byronic hero: he forgot to confess his crimes, so it is on her wedding day that she discovers there is someone in the chapel who knows a reason that she and Rochester can't be married. It is Edward Mason, brother to Bertha, the mad wife who still lives at the top of the stairs. Rochester's redemption must be delayed for another half the book.

To start, Mr. Rochester is the typical Byronic hero but tamer than Heathcliff because he has an estate and a reputation to keep up. He has several crimes he's keeping secret; first, there's the parentage of the charming Adele who Jane is brought in to care for. But much more significantly there's the mad wife he keeps locked on the third floor, giving the first half of the novel its Gothic undertones. He is arrogant, almost running Jane down on her way to his manor and cursing her for getting in his way. He is curt to her--and to almost everyone--brooding alone in his study most evenings when he is at home. Jane is meant to be his salvation but he has forgotten an important step in the reclamation of the Byronic hero: he forgot to confess his crimes, so it is on her wedding day that she discovers there is someone in the chapel who knows a reason that she and Rochester can't be married. It is Edward Mason, brother to Bertha, the mad wife who still lives at the top of the stairs. Rochester's redemption must be delayed for another half the book.

Edward as Rochester; Bella as Jane

- Both Jane and Bella make their own way in the face of bad/no parenting. Both consider themselves ordinary, even plain. Bella's mom thinks she's an 'old soul'. The same might be said for Jane Eyre.

- Edward and Rochester are handsome, curt, dismissive, even cruel to the young women as they suffer and brood, keeping their sins a secret. Both are 'older men' to the young woman.

- Both learn to trust and love the woman in their lives through talk (see the third picture LEFT). Both men consider her special, no matter how often this surprises her. (In both cases, the story is told from her point of view.)

- There is a love match/almost-wedding, after which things in the relationship go very wrong. A dire split occurs.

- Both young women are beginning to make their way in a new life with new loves . . .

- When a call comes, summoning her to help. Edward is in the hands of the Volturi and Rochester is hurt, blinded and financially ruined when Bertha destroys herself and the manor in a conflagration.

- The young woman must not just save the despairing soul of the Byronic hero, she must save his life as well. (Pattinson, for all his height and body mass, looks as vulnerable and captive as any damsel-in-distress, pinioned as he is in the bottom photo. And the only one who can save him is little Bella. She gets the opportunity that is, supposedly, 'what women want': to save her man.) Jane Eyre knows how to survive on little and, when they are married now in honesty, she will be Rochester's eyes, his guide. She will run the manor--or what's left of it. Edward too proposes marriage after Bella saves him, recognizing that he owes her trust as well as love.

*FOOTNOTE: What makes the Byronic Hero so appealing to female readers is not the bad-boy thing at all. It's the reverse-Eden story. For centuries of rampant Christanity and, incidentally, male-domination, everyone was taught that Eve--inferior, rib-born Eve--was responsible for the Fall of Man and that her first reaction to knowing sin was to drag Adam down too. Part of that teaching said that woman had to look for her instruction in morality to her Adam; he would look to God and she, to the God in him. It took Jesus (a man, of course) to set things right--get us a chance at paradise again, even if only after death (which of course weak little Eve brought into the world).

How liberating it is if Eve gets to move outside of ancient parameters, save the Satan-like character and make a new kind of paradise! Leave goofy, whiny Adam and boring, pedantic God to complain about her in the old Eden--she gets a fresh start as a vampire, a ghost, the mistress of an estate, whatever. (And that too fits with the Lilith archetype--more later.) No wonder the Byronic hero stories are fiction that appeals to women and doesn't appeal to men. The Byronic hero challenges the right of supremacy of the descendants of Adam in the ordinary world. Mike Newton, go home!

Problem is RPattz disparages it too, and it's not objectionable because he bites the hand that feeds him; it's that, like every other boyfriend, he's willing to tow the line that the Byronic hero is 'sucky'. Put women back in their places. Let me do a movie that's funny, he says--like something from Judd Apatow (usually anti-woman)--or a gangster role (movies that either lack women or she's a dupe of some kind, killed by the end of the second reel)--so I can make the boys in the schoolyard like me again. (He'd do better sticking to 'type'. If he wants to escape seeming to be the pained lover all the time--"Remember Me", "Water for Elephants"--he should try Shakespeare. And the perfect role--still compassionate, long-suffering, hard-done-by [and mad], but not a girlfirend in sight--would be Edgar in "King Lear". There's acting chops for you--and like Daniel Radcliffe, he could do it on stage. Can our "I don't do homework but I finished my O levels" boy handle it?)

When you hear Kristen Stewart talk about the movies, she always seems a little too serious--I think I've made fun of her for it, basically because I was still rejecting Stephenie Meyer as a writer. But she's maybe got it right. And maybe so many sites make fun of her monotone and her twitchy acting because she does have so much to say about the importance of Bella in a young girl's life. The 'boys' do character assassination very well.

How liberating it is if Eve gets to move outside of ancient parameters, save the Satan-like character and make a new kind of paradise! Leave goofy, whiny Adam and boring, pedantic God to complain about her in the old Eden--she gets a fresh start as a vampire, a ghost, the mistress of an estate, whatever. (And that too fits with the Lilith archetype--more later.) No wonder the Byronic hero stories are fiction that appeals to women and doesn't appeal to men. The Byronic hero challenges the right of supremacy of the descendants of Adam in the ordinary world. Mike Newton, go home!

Problem is RPattz disparages it too, and it's not objectionable because he bites the hand that feeds him; it's that, like every other boyfriend, he's willing to tow the line that the Byronic hero is 'sucky'. Put women back in their places. Let me do a movie that's funny, he says--like something from Judd Apatow (usually anti-woman)--or a gangster role (movies that either lack women or she's a dupe of some kind, killed by the end of the second reel)--so I can make the boys in the schoolyard like me again. (He'd do better sticking to 'type'. If he wants to escape seeming to be the pained lover all the time--"Remember Me", "Water for Elephants"--he should try Shakespeare. And the perfect role--still compassionate, long-suffering, hard-done-by [and mad], but not a girlfirend in sight--would be Edgar in "King Lear". There's acting chops for you--and like Daniel Radcliffe, he could do it on stage. Can our "I don't do homework but I finished my O levels" boy handle it?)

When you hear Kristen Stewart talk about the movies, she always seems a little too serious--I think I've made fun of her for it, basically because I was still rejecting Stephenie Meyer as a writer. But she's maybe got it right. And maybe so many sites make fun of her monotone and her twitchy acting because she does have so much to say about the importance of Bella in a young girl's life. The 'boys' do character assassination very well.

Several pictures above are from the Everglow Image Gallery at www.edwardandbella.net.

Please go back to the Navigation Bar (above) for additional pages in the Edward Cullen literary ancestry story.

Please go back to the Navigation Bar (above) for additional pages in the Edward Cullen literary ancestry story.