THE LITERARY HISTORY

In order to figure out why Edward Cullen is so appealing, we have to go quite far back in time--to an ARCHETYPE in literature that was created, to some degree, by accident. John Milton (1608-1674) is probably considered, after Shakespeare, to be our greatest poet/author in English Lit and his most famous work by far is Paradise Lost, a staple in Christian households probably until well into the 20th Century. So that would mean that everyone knew it, perhaps even better than they knew the Bible.

In it, Milton, by his own admission, wants to "justify the ways of God to man", so in this very long (epic) narrative poem, he covers the fall of the rebel angels, the creation of Adam and Eve, Satan's revenge, debates in Heaven about all kinds of things: sin, marriage, good and evil, the redemption of man etc. It's clear that Milton wants to make the Heavenly debates the most compelling part of the poem so that, as good Christians all, we would want to join that God-led circle someday. Problem: it is not the most interesting part of the poem. As William Blake said of Paradise Lost, "Milton was of the Devil's party without knowing it," meaning that Milton wrote about Satan with energy and verve, making him come to life, whereas the Heavenly company sound like a particularly boring faculty of Philosophy with a pedantic and dictatorial head.

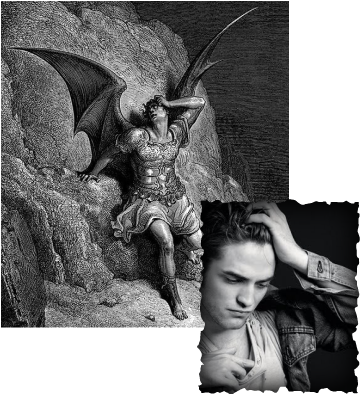

AT FAR LEFT you see an engraving by Gustave Dore interpreting Milton's Satan some two hundred years after Paradise Lost was published, but it gives you the idea of what Milton's anti-hero (Anti-Christ) had become to readers: a brooding figure who had suffered much and was driven to torment others only because of his own pain. NEAR LEFT, Robert Pattinson in one of those brooding, smouldering photos. Note similarities in pose and expression.

In it, Milton, by his own admission, wants to "justify the ways of God to man", so in this very long (epic) narrative poem, he covers the fall of the rebel angels, the creation of Adam and Eve, Satan's revenge, debates in Heaven about all kinds of things: sin, marriage, good and evil, the redemption of man etc. It's clear that Milton wants to make the Heavenly debates the most compelling part of the poem so that, as good Christians all, we would want to join that God-led circle someday. Problem: it is not the most interesting part of the poem. As William Blake said of Paradise Lost, "Milton was of the Devil's party without knowing it," meaning that Milton wrote about Satan with energy and verve, making him come to life, whereas the Heavenly company sound like a particularly boring faculty of Philosophy with a pedantic and dictatorial head.

AT FAR LEFT you see an engraving by Gustave Dore interpreting Milton's Satan some two hundred years after Paradise Lost was published, but it gives you the idea of what Milton's anti-hero (Anti-Christ) had become to readers: a brooding figure who had suffered much and was driven to torment others only because of his own pain. NEAR LEFT, Robert Pattinson in one of those brooding, smouldering photos. Note similarities in pose and expression.

How did we get this 'romantic' archetypal image of Satan?

Here's RPattz in a familiar pose:

Notice any similarities??

First of all, there's not actually much about Satan/Lucifer/ the Anti-Christ in the Bible until you get to that garbled and deliberately cryptic mess at the end of the New Testament called Revelation. (It would behoove everybody to learn how John of Patmos came to write that thing--though it would ruin all future apocalyptic, biblically-inspired horror movies if we did. . . .) He's most prominent in the book of Job where he most definitely is at God's side. In fact his name means "the accuser", rather like a prosecuting attorney. A passing reference in the book of Isaiah to 'Lucifer' and how long in took for him to fall (most scholars think this refers to a local king, rather than any immortal figure) gave birth, in post-biblical times, to a fascinating story about how Lucifer was once an archangel who rebelled against God and was thrown out, along with his fellow rebel angels. 'Lucifer' (meaning 'light-bearer') was, according to this myth, the devil's name when he was beautiful, a heavenly archangel; 'Satan' (Beelzebub, Mephistopheles), the name he was known by after God carved out a particularly wretched part of the universe called Hell for him and his fellow rebels. That story was widely known (though, again, not appearing in the Bible), used by countless preachers to summon up fear in their congregations by invoking 'hellfire and brimstone', but Milton really runs with it. (It likely had never been assembled in cogent story-form before.)

The first two books of Paradise Lost, where Satan wakes up, apparently right after his defeat, are dynamite. Milton opens with Satan rising amidst the hellish lake of fire where "he with his horrid crew lay vanquisht, rolling in the fiery gulf, confounded though immortal." So far, he's only immortal and doomed--exactly what we would expect, given the circumstances, but Milton gives us more: "Now the thought both of lost happiness and lasting pain torments him; round he throws his baleful eyes that witness'd huge affliction and dismay, mixt with obdurate pride and stedfast hate." We have the makings here of every pained, smouldering rebel from Heathcliff to Edward Cullen: the monster who must live apart from the society he craves because of the horror he's seen (or committed--some of our rebels are evil) and that pain leads him to sins of both pride and hate.

The first two books of Paradise Lost, where Satan wakes up, apparently right after his defeat, are dynamite. Milton opens with Satan rising amidst the hellish lake of fire where "he with his horrid crew lay vanquisht, rolling in the fiery gulf, confounded though immortal." So far, he's only immortal and doomed--exactly what we would expect, given the circumstances, but Milton gives us more: "Now the thought both of lost happiness and lasting pain torments him; round he throws his baleful eyes that witness'd huge affliction and dismay, mixt with obdurate pride and stedfast hate." We have the makings here of every pained, smouldering rebel from Heathcliff to Edward Cullen: the monster who must live apart from the society he craves because of the horror he's seen (or committed--some of our rebels are evil) and that pain leads him to sins of both pride and hate.

But where does the girl come into it?

You may remember that Stephenie Meyer uses a quotation from Genesis (where God tells Adam they may not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil) as the epigraph for Twilight, implying that for Bella to fall for Edward will be her own fall from grace, will provide her with her own knowledge of good and, by her introduction into the vampire's world, evil. But the book cover shows a girl's hands holding out the apple of temptation, just as Eve tempted Adam in the Garden of Eden. Then, by analogy, it's implied that Edward is a sort of goofy Adam and Bella, an already tainted temptress who wants to lead him away from grace. (Feels more like RPattz and KStew, doesn't it? Especially if fame--or sorry, 'acting' chops is the temptation.) Director Catherine Hardwicke sets it right again in the movie when she has Edward hold out Bella's fallen apple. He's our romantic, suffering anti-hero. He's our Miltonic Satan. As he tells her himself, "What if I'm not the superhero? What if I'm the bad guy?"

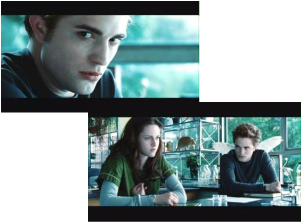

AT LEFT are two stills from the movie where Catherine Hardwicke consciously pushes the identification of Edward Cullen with the brooding anti-hero, the fallen archangel. As Cullen tells Bella in the book, he hated her in that first classroom scene, wanted to kill her, to take her right then and there, in front of all those children. Note the way the stuffed owl's wings are positioned behind his shoulders in the second picture. His eyes are dark, his sweater is charcoal and Bella tells us that his first glance at her was the embodiment of "if looks could kill". The movie in particular emphasizes the darkness in this seduction: in the book Cullen, with his constant, imperious smirk, could be the masochistic 'lion' who falls in love with the 'lamb'; Hardwicke takes it back to first cases--it is Eve/Bella who willingly wants to save our self-tormenting young Satan from himself.

AT LEFT are two stills from the movie where Catherine Hardwicke consciously pushes the identification of Edward Cullen with the brooding anti-hero, the fallen archangel. As Cullen tells Bella in the book, he hated her in that first classroom scene, wanted to kill her, to take her right then and there, in front of all those children. Note the way the stuffed owl's wings are positioned behind his shoulders in the second picture. His eyes are dark, his sweater is charcoal and Bella tells us that his first glance at her was the embodiment of "if looks could kill". The movie in particular emphasizes the darkness in this seduction: in the book Cullen, with his constant, imperious smirk, could be the masochistic 'lion' who falls in love with the 'lamb'; Hardwicke takes it back to first cases--it is Eve/Bella who willingly wants to save our self-tormenting young Satan from himself.

How is Milton's Satan self-tormenting?

Once he's away from his fellow minions in Hell, having promised them he'll wreak vengeance on an all-powerful God the only way he can--by destroying his newly-created humans--he has multiple second thoughts, much as Edward spends a good part of the early scenes in both book and movie telling Bella it's not good for them to be friends.

Speaking to himself, Satan says, "Ay me, they little know under what torments inwardly I groane: while they adore me on the Throne of Hell, the lower still I fall, only supreme in miserie." When he first sees Adam and Eve in all their innocence, he says to himself he should "at your harmless innocence melt, as I do," but revenge "compels me now to do what else, though damnd, I should abhor." When confronted by the presence of one who is truly good, Milton gives us this description: "abash'd the Devil stood, and felt how awful goodness is, and saw Virtue in her shape how lovely, saw, and pin'd his loss."

And, as with Edward Cullen, confronting Eve (Bella) and her innocence brings out Satan's desire to turn away from her in her best interest: "Her graceful Innocence, her every air of gesture or least action overawed his Malice, and bereav'd his fierceness of the fierce intent it brought: in that space the Evil one abstracted stood from his own evil, and for the time remaind stupidly good", disarmed of guile, hate, envy, revenge.

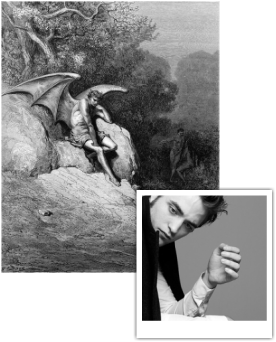

FAR LEFT shows a Dore illustration from Book 9 of Paradise Lost; Satan broods over how he feels and what he should do, with Adam and Eve in the background. LEFT is Rob Pattinson in a similar pose.

Speaking to himself, Satan says, "Ay me, they little know under what torments inwardly I groane: while they adore me on the Throne of Hell, the lower still I fall, only supreme in miserie." When he first sees Adam and Eve in all their innocence, he says to himself he should "at your harmless innocence melt, as I do," but revenge "compels me now to do what else, though damnd, I should abhor." When confronted by the presence of one who is truly good, Milton gives us this description: "abash'd the Devil stood, and felt how awful goodness is, and saw Virtue in her shape how lovely, saw, and pin'd his loss."

And, as with Edward Cullen, confronting Eve (Bella) and her innocence brings out Satan's desire to turn away from her in her best interest: "Her graceful Innocence, her every air of gesture or least action overawed his Malice, and bereav'd his fierceness of the fierce intent it brought: in that space the Evil one abstracted stood from his own evil, and for the time remaind stupidly good", disarmed of guile, hate, envy, revenge.

FAR LEFT shows a Dore illustration from Book 9 of Paradise Lost; Satan broods over how he feels and what he should do, with Adam and Eve in the background. LEFT is Rob Pattinson in a similar pose.

Is the anti-hero Satan meant to be good-looking?

It's Shakespeare himself who has Hamlet tell us 'the devil has powers to assume a pleasing shape' (indeed, if he weren't so obsessed with his mother and dad, Hamlet could be the first of our brooding anti-heroes), but it was a long-standing theological tradition that the devil would come to us using all his wiles, beauty being one. Though the following is a description of Milton's Satan after he enters the snake, this is one beautiful serpent: "his head crested aloft, and carbuncle his eyes; with burnisht Neck of verdant Gold, erect amidst his circling coils, that on the grass floated redundant: pleasing was his shape, and lovely." As in the 'golden eyes' scene depicted at left, Edward is indeed pleasing to look at. According to Hardwicke, she liked the fact that Rob Pattinson is both handsome and menacing; look at the 1/8th profile in the bottom-right shot. Though he's usually criticized for having a too-small range of moods, his face is expressive enough to fit even Milton's criteria for Satan: "each passion dimm'd his face; thrice chang'd with pale ire, envie and despair, which marr'd his visage, yet seemd undaunted."

Meyer has Edward tell Bella that himself: everything about him--his face, his voice, his smell--is meant to lure her in. But whereas in the novel he is only momentarily threatening, Hardwicke does a better job with this scene. From the moment he follows Bella into the woods, he is menacing. The lines "Say it. Aloud. Say it," though not in the novel at all, stuck so well in my mind, I guess from the trailer, that it seems the only way that scene could be played. (I was shocked, going back to the novel, that they weren't there.) In forcing her to confront what he is--and not just repeat the story Jacob told her, as in the novel--Edward's villainy is reinforced at a key moment. It's like the dangling strawberry in Polanski's "Tess" or in "9 1/2 Weeks"--the man pushing the woman in a direction she doesn't want to go, a direction that is both sado-masochistic and sexual at the same time. And Pattinson plays the whole scene as the controller; his viciousness is not understated. He wants her to go away.

One part of the 'lore' of this movie is that Kristen Stewart auditioned with Rob Pattinson and picked him over the others because, along with the confidence and the menace, he showed some vulnerability--that he wasn't always sure of his judgements. I never fail to be amazed that some feminists decry how weak Bella is--maybe in later books of the series, but in this scene she physically steps into his space and pushes him back into the tree while telling him she knows he won't hurt her, when every piece of evidence he has given to her would tend to scream the opposite. Sure, the context is all romance, but that's true for Edward as well; the object for both parties in this drama is to get together safely on the other side. So Eve/Bella doesn't just fall into the trap of the villainous serpent, eat the apple and go running off to implicate some other hapless human to share the blame; she embraces Satan, therefore not only having knowledge of the 'evil' but wanting to become it herself, for his sake--risking her own soul to prove he has one.

Meyer has Edward tell Bella that himself: everything about him--his face, his voice, his smell--is meant to lure her in. But whereas in the novel he is only momentarily threatening, Hardwicke does a better job with this scene. From the moment he follows Bella into the woods, he is menacing. The lines "Say it. Aloud. Say it," though not in the novel at all, stuck so well in my mind, I guess from the trailer, that it seems the only way that scene could be played. (I was shocked, going back to the novel, that they weren't there.) In forcing her to confront what he is--and not just repeat the story Jacob told her, as in the novel--Edward's villainy is reinforced at a key moment. It's like the dangling strawberry in Polanski's "Tess" or in "9 1/2 Weeks"--the man pushing the woman in a direction she doesn't want to go, a direction that is both sado-masochistic and sexual at the same time. And Pattinson plays the whole scene as the controller; his viciousness is not understated. He wants her to go away.

One part of the 'lore' of this movie is that Kristen Stewart auditioned with Rob Pattinson and picked him over the others because, along with the confidence and the menace, he showed some vulnerability--that he wasn't always sure of his judgements. I never fail to be amazed that some feminists decry how weak Bella is--maybe in later books of the series, but in this scene she physically steps into his space and pushes him back into the tree while telling him she knows he won't hurt her, when every piece of evidence he has given to her would tend to scream the opposite. Sure, the context is all romance, but that's true for Edward as well; the object for both parties in this drama is to get together safely on the other side. So Eve/Bella doesn't just fall into the trap of the villainous serpent, eat the apple and go running off to implicate some other hapless human to share the blame; she embraces Satan, therefore not only having knowledge of the 'evil' but wanting to become it herself, for his sake--risking her own soul to prove he has one.

Is the brooding anti-hero never satisfied with his choices?

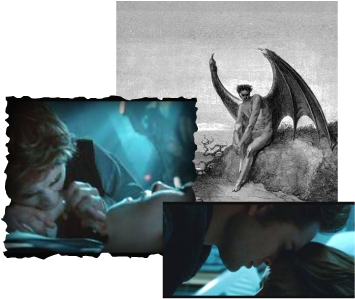

All the anti-heroes in literature I'll be discussing suffer monumentally in body and/or soul, even unto death. (Some wish for death, like Edward in "New Moon", but because of their power cannot die.) But with both Cullen and Milton's Satan, there is an earlier moment when he decides on a fateful course after going through at least some of the self-torment. Milton has Satan say, "Farewel, Remorse! All Good to me is lost. Evil, be thou my Good." And as the picture NEAR LEFT depicts, when Edward walks into the school with Bella after admitting he's a vampire, he says, "I'm going to Hell anyway," and for a moment enjoys being able to declare himself.

In "Twilight's" inverted good/evil paradigm, the object for Satan and his Eve is to create a paradise that they deserve. The recurring meadow motif is certainly one Garden of Eden image that usually indicates a positive step in the affirmation of their relationship. But more potently, Hardwicke adds a rather long scene that is not in the novel in any form: "Hold on, spider monkey," says Edward and takes her to the top of an ancient pine for a God's-eye view of the Pacific northwest (see photo, FAR LEFT). This is impossible, she exclaims to him. It can't be real. "It is in my world," he answers, and we have what, if these anti-hero stories ever worked out right, should be the climax--Satan and his Eve climbed the tree of knowledge of good and evil and got their Eden, seemingly without taint. Our Satan/Edward has replaced God in Bella's contemporary world and, if he doesn't have a soul, it doesn't seem to detract from his world's appeal. (Indeed, in inverting the original paradigm again, though Adam and Eve lost immortality by eating the fruit of the tree, Bella can regain it, as Edward has, if she can just talk him into turning her.) Later in the novel (it's at the beginning of the movie "New Moon"), she goes so far as to say, "If it's my soul you're worried about, don't. I don't care about it." Not so strange for a modern girl but pretty strange for the Mormon-educated author of these books.

But even in an inverted paradise, there's going to be trouble and it springs directly from the fact that Edward has so successfully overcome his hate and murderous tendencies toward his Eve/Bella that he can take her out for some good, clean fun. Vampires, though, are mostly still just plain evil and, as he is forced to save her a third time in this story, he is tested again and despairs of ever being able to make her safe and happy (and therefore of ever deserving her). That sends him back to his brooding, self-tormented ways. (This return to despair doesn't just foreshadow the controlling plot of "New Moon"; it essentially drives the plots of all the remaining books--until Bella, increasingly capable of saving him in return, becomes a kind of 'superhero' herself in "Breaking Dawn" and can save everyone else about whom she cares.)

In "Twilight's" inverted good/evil paradigm, the object for Satan and his Eve is to create a paradise that they deserve. The recurring meadow motif is certainly one Garden of Eden image that usually indicates a positive step in the affirmation of their relationship. But more potently, Hardwicke adds a rather long scene that is not in the novel in any form: "Hold on, spider monkey," says Edward and takes her to the top of an ancient pine for a God's-eye view of the Pacific northwest (see photo, FAR LEFT). This is impossible, she exclaims to him. It can't be real. "It is in my world," he answers, and we have what, if these anti-hero stories ever worked out right, should be the climax--Satan and his Eve climbed the tree of knowledge of good and evil and got their Eden, seemingly without taint. Our Satan/Edward has replaced God in Bella's contemporary world and, if he doesn't have a soul, it doesn't seem to detract from his world's appeal. (Indeed, in inverting the original paradigm again, though Adam and Eve lost immortality by eating the fruit of the tree, Bella can regain it, as Edward has, if she can just talk him into turning her.) Later in the novel (it's at the beginning of the movie "New Moon"), she goes so far as to say, "If it's my soul you're worried about, don't. I don't care about it." Not so strange for a modern girl but pretty strange for the Mormon-educated author of these books.

But even in an inverted paradise, there's going to be trouble and it springs directly from the fact that Edward has so successfully overcome his hate and murderous tendencies toward his Eve/Bella that he can take her out for some good, clean fun. Vampires, though, are mostly still just plain evil and, as he is forced to save her a third time in this story, he is tested again and despairs of ever being able to make her safe and happy (and therefore of ever deserving her). That sends him back to his brooding, self-tormented ways. (This return to despair doesn't just foreshadow the controlling plot of "New Moon"; it essentially drives the plots of all the remaining books--until Bella, increasingly capable of saving him in return, becomes a kind of 'superhero' herself in "Breaking Dawn" and can save everyone else about whom she cares.)

Must the brooding anti-hero always succumb to despair?

Alas, he must. Though, unlike Edward Cullen, Milton's Satan has committed himself to evil, it is nonetheless true that his choices and his deeds make him aware that he carries Hell around inside him all the time; he is Hell. That is shown quite graphically in the Dore illustration at the LEFT. And Cullen in the movie seems far less able to stop when he bites Bella than he did in the novel; Hardwicke has Carlisle yelling at him to stop as Edward's face contorts with the feeding frenzy he always feared and Bella sinks into a montage of before-death flashbacks. No wonder then that he tries to say good-bye in the hospital, but Bella won't let him. "Where would I go?" he promises, but with a sigh of regret that tells us he is deeply conflicted again.

In the novel, Bella knows very little of what is going on around her as she writhes in agony. Hardwicke, though, wants to remind us one more time that vampires, by their 'birth', are evil. As Pattinson plays him, Cullen is hardly human as he bites flesh out the tracker vampire, James. We catch a glimpse of sweet little Alice in inhuman contortions on James' shoulders as she rips off his head. And the scene of the Cullens in deep shadow dancing with glee around the inferno as their enemy burns is meant to evoke an image of Hell--and is so important that Hardwicke uses the same footage to play on the TV in Bella's hospital room. (Is she saying that we take hellfire and brimstone in our TV and movies so casually--just as Bella does her soul--we might as well be living in, fully embracing Hell? Yet another point that this movie is about the fall of all of us from innocence into a knowledge of good and evil--and an acceptance of both.)

In the novel, Bella knows very little of what is going on around her as she writhes in agony. Hardwicke, though, wants to remind us one more time that vampires, by their 'birth', are evil. As Pattinson plays him, Cullen is hardly human as he bites flesh out the tracker vampire, James. We catch a glimpse of sweet little Alice in inhuman contortions on James' shoulders as she rips off his head. And the scene of the Cullens in deep shadow dancing with glee around the inferno as their enemy burns is meant to evoke an image of Hell--and is so important that Hardwicke uses the same footage to play on the TV in Bella's hospital room. (Is she saying that we take hellfire and brimstone in our TV and movies so casually--just as Bella does her soul--we might as well be living in, fully embracing Hell? Yet another point that this movie is about the fall of all of us from innocence into a knowledge of good and evil--and an acceptance of both.)

But doesn't "Twilight" at least have a happy ending?

Actually, Paradise Lost has the happy ending--if not truly contained within the poem (although we have met the archangel who has volunteered to be the Christ during one of the Heavenly staff meetings), it will occur in the unfinished sequel, Paradise Regained. Milton knows that all his Christian readers are aware of a much simpler universe: Satan, after much torment and despair, has committed himself to mankind's doom and is now the embodiment of evil; the Christ will allow himself to become a Son of Man and die on the cross to redeem us--to save our souls--representing in that way the ultimate good.

Bella seems to get a happy ending--though she resents the prom in many ways. But as the series of photos on the NEAR LEFT show, there's another agenda on the docket and it confuses us--and Edward--about what happiness for Bella is. In the novel, the scene where she asks to be changed, right there at the prom, is almost silly and we don't believe that the smirking, know-it-all Cullen in the book is seriously tempted any longer. We are not remotely fearful as he plants a kiss instead of his teeth on her throat.

But again Hardwicke makes the situation much more tense and, to give credit where it's due, Pattinson's infinitely changeable face contributes to the suspense. After all, in one sense, Edward is her saviour: not just because he rescues her from all the big and little threats she is subject to, but because in the Satan-Eve paradigm, he has brought her to the brink of a paradise which might include regaining immortality in a meaningful way. But he is still a vampire--intrinsically evil, a monster, and perhaps soulless. When she exposes her throat, Pattinson, looking mature well beyond his years and rather threateningly exotic, sucks in his cheeks and appears to be seriously contemplating taking her at last. Hardwicke has him bend in to Bella's long, vulnerable neck in what is almost slow motion (in the DVD commentary, the three of them are dead quiet until Hardwicke breathes, "This is so hot") and, though we have read the book, for that moment, we really don't know which of the three choices he will make--or which we want him to make.

I think it's significant that there have been no mutual declarations of love in the movie; Edward hasn't sat with her in the rocking chair saying, "You are my life now." By omitting those parts of the book, there are an array of futures possible here at the climax. When he turns what might have been a radical change for Bella into a chaste though lingering kiss, we are almost disappointed--as she clearly is. What is absolutely fascinating is what Pattinson does at this moment: no smirking superciliousness for the movie Cullen. When he raises his head to speak, he seems tearful, almost broken. I suspect--and this is because of his self-tormenting anti-hero status--that he despairs of his own self-control and of his ability to save her soul, if she demands the change again and again (as of course she does). Though he loves her, she has now become his chief source of torment beyond his own mind. He can't leave her (though he will try) and yet he can't truly save her in a paradise that is of their own making.

Another piece of evidence of the importance of Bella's stature in the movie version is that she is given what are Cullen's lines in the book. It is enough for now that they will enjoy each other in the various lives that have been given to them--but not enough forever. When that's Edward's line, he holds all the cards; when they're hers, she's giving into him 'for now' because she senses his suffering and his ambivalence. But she intends to force the issue again, perhaps when he is more at peace.

Several pictures above are from the Everglow Image Gallery at www.edwardandbella.net.

Please go back to the Navigation Bar (above) for additional pages in the Edward Cullen literary ancestry story.

Bella seems to get a happy ending--though she resents the prom in many ways. But as the series of photos on the NEAR LEFT show, there's another agenda on the docket and it confuses us--and Edward--about what happiness for Bella is. In the novel, the scene where she asks to be changed, right there at the prom, is almost silly and we don't believe that the smirking, know-it-all Cullen in the book is seriously tempted any longer. We are not remotely fearful as he plants a kiss instead of his teeth on her throat.

But again Hardwicke makes the situation much more tense and, to give credit where it's due, Pattinson's infinitely changeable face contributes to the suspense. After all, in one sense, Edward is her saviour: not just because he rescues her from all the big and little threats she is subject to, but because in the Satan-Eve paradigm, he has brought her to the brink of a paradise which might include regaining immortality in a meaningful way. But he is still a vampire--intrinsically evil, a monster, and perhaps soulless. When she exposes her throat, Pattinson, looking mature well beyond his years and rather threateningly exotic, sucks in his cheeks and appears to be seriously contemplating taking her at last. Hardwicke has him bend in to Bella's long, vulnerable neck in what is almost slow motion (in the DVD commentary, the three of them are dead quiet until Hardwicke breathes, "This is so hot") and, though we have read the book, for that moment, we really don't know which of the three choices he will make--or which we want him to make.

I think it's significant that there have been no mutual declarations of love in the movie; Edward hasn't sat with her in the rocking chair saying, "You are my life now." By omitting those parts of the book, there are an array of futures possible here at the climax. When he turns what might have been a radical change for Bella into a chaste though lingering kiss, we are almost disappointed--as she clearly is. What is absolutely fascinating is what Pattinson does at this moment: no smirking superciliousness for the movie Cullen. When he raises his head to speak, he seems tearful, almost broken. I suspect--and this is because of his self-tormenting anti-hero status--that he despairs of his own self-control and of his ability to save her soul, if she demands the change again and again (as of course she does). Though he loves her, she has now become his chief source of torment beyond his own mind. He can't leave her (though he will try) and yet he can't truly save her in a paradise that is of their own making.

Another piece of evidence of the importance of Bella's stature in the movie version is that she is given what are Cullen's lines in the book. It is enough for now that they will enjoy each other in the various lives that have been given to them--but not enough forever. When that's Edward's line, he holds all the cards; when they're hers, she's giving into him 'for now' because she senses his suffering and his ambivalence. But she intends to force the issue again, perhaps when he is more at peace.

Several pictures above are from the Everglow Image Gallery at www.edwardandbella.net.

Please go back to the Navigation Bar (above) for additional pages in the Edward Cullen literary ancestry story.